I have always needed to draw.

As a kid, my pencil would devour reams of paper. Fantastic worlds and fictional characters were but a few pencil marks away. Even today, my binders and notebooks are decorated with absent minded doodles and geometric designs. Yes, somewhat cliché, but drawing has always been an escape for me, a way to step away from this world and, on a 8 ½ by 11 sheet of paper, enter a new one.

For me, drawing has always had a strange dichotomy. A conflict, a balance between representation and imagination. Technique versus concept. On one hand, drawing is an empirical process, for to be a good drawer, one must master observation. A family friend, a sculptor and painter, would always tell me that drawing was “learning how to see.” Drawing, especially from life, trains your eye to notice changes in value, negative space, angles and perspective; by transferring what you see onto paper, you force yourself to dispel any preconceptions of what something should look like and focus on the form you actually want to represent. The flower in a still life is no longer a stereotypical “flower” but rather a complex collection of forms, of nuanced curves and of unique values. As an exercise in my high school art classes, my teacher would have us practice blind contour-line drawings of objects, or even of other classmates. The rules were simple—your pen could not leave the paper and you could not look at your drawing—and our initial results would more resemble organic blobs or horrendously distorted faces than the actual subject of our drawing. But upon second glance, these drawings were often more accurate than those one would produce if asked to draw something from imagination. Lines veering off to seemingly nowhere were actually explorations of form (perhaps of the folds of the ear, or of a wrinkle in the still-life drapery). To master these drawings, one needed to force their eyes to explore every aspect of the subject, and coordinate their pen (yes, pen made these drawings all the more permanent and humiliating) to “move at the same speed as their eyes”. Drawing allows you to deconstruct what you see into lines and values, and then synthesize these parts into a whole.

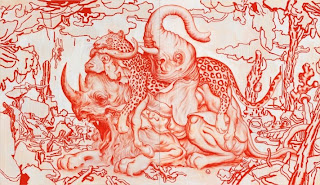

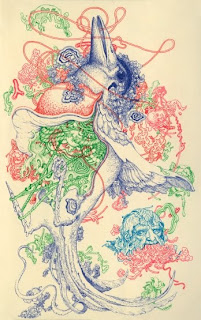

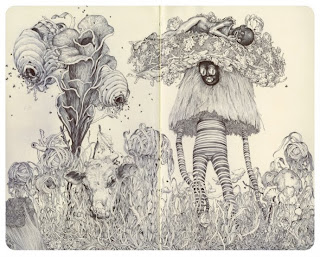

Observation is only a starting point though. It is easy enough to copy a picture or draw a still life, but I have always had trouble extrapolating from reality, creating imaginative images that maintain the realistic detail of an observational drawing. As well-rendered or photorealistic an observational drawing may be, it may still lack the depth of content or style which give any piece of art its “ummph.” Manipulation of marks is one method to achieve this depth; though more easily done with paint, expressive mark making in drawing can direct energy or guide the viewer’s eye. But more, the concept of a piece, or even just its bizarreness, provokes a greater response from the viewer. The artist James Jean is my artistic idol in this area; his pieces, still completed with masterful technique, abound with exuberant creativity. He juxtaposes images and manipulates forms, his pieces generally whimsical and at times almost appearing cartoon-esque, yet he accentuates his subjects with intricate line and engaging compositions. (I have included some of my favorite drawings/paintings of his).

Drawing isn’t my favorite media, but I compare it to working out. It is something you need to practice to get better at, and is an activity and skill without which one will not achieve comparable depth and richness in other work.

No comments:

Post a Comment