Circle Limit III, 1959. Woodcut, second state, in yellow, green, blue, brown, and black, printed from five blocks.

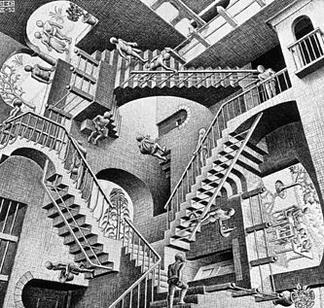

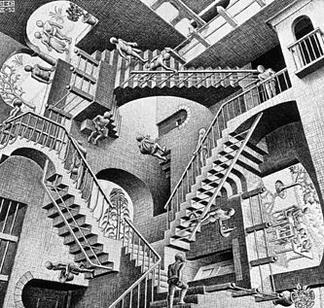

Relativity. 1953. Lithograph.

Drawing Hands, 1948. Lithograph.

M. C. Escher, whose full name was Maurits Cornelis Escher, was born on June 17, 1898 in Leeuwarden, Netherlands, and died March 27, 1972 in Laren. He was a graphic artist best known for his realistic prints that played with weird optical and surreal effects. He used lithographs, woodcuttings, and engravings to portray "impossible" spaces. In 1919, he attended the Haarlem School of Architecture and Decorative Arts. He began studying architecture, but then switched to decorative arts, where he studied under Samuel Jessurum de Mesquita. One of the reasons he turned to art was that he felt images were the best way for communicating his ideas to other people; they were graphic, not literary, concepts. He left the school in 1922 and traveled through Italy and Spain. He met Jetta Umiker in Italy and married her later in 1924. They lived in Rome until 1935, when the political tension caused by Mussolini drove them to leave for Switzerland. They had a son in Rome, named Giorgio Arnaldo Escher. They moved again in 1937 to a town near Brussels, but then, in 1941, World War II forced them to move to the Netherlands, where Escher remained until 1970. Most of Escher's more famous works come from this period. In 1970 he moved to a retirement home for artists in Laren, and he died there in 1972.

His art is also known for its unique mathematical qualities, and his work in fact has influenced the field of mathematics. He portrayed mathematical relationships between figures, places, and space. One of his greatest mathematical interests was in regular division of planes and symmetry. Escher was influenced by George Polya's academic writings on plane symmetry groups, which his brother, Berend, sent to him. This inspired Escher to more heavily incorporate mathematics into his art, starting in 1937. In 1941, Escher wrote his own paper, Regular Division of the Plane with Asymmetric Congruent Polygons, detailing his mathematical approach to art. In this paper, he studied color-based division, and developed a system of categorizing different combinations of color, shape, and symmetrical properties. This area was later labeled crystallography by mathematicians. Escher also experimented with other mathematical concepts in the 50s, such as representing infinity on a two-dimensional plane.

I was interested in Escher's art because it portrays an "alternate" reality in which the laws of the world we live in don't seem to apply. I always felt that one of the most beautiful qualities of art was that it could be used to distort, skew, and create new worlds. I think Escher's application of math to art is intriguing because, so often, they are viewed as being opposites, with math as a rational force and art as an irrational, emotional one. Thus, his combination of the two brings a fresh perspective to art.

Bibliography:

Maurits Cornelis Escher. M. C. Escher: The Graphic Work. Taschen, Germany. 2001.

"M.C. Escher." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 28 Oct. 2010 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/192344/M-C-Escher>.

"M. C. Escher." Wikipedia.org. 28 Oct 2010. < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MC_Escher>

Aesthetically, scenes from Kon's films are typically colorful and visually effective. Kon's later films layer backgrounds and lighting to create papery u-kyoe effects, heavy silhouettes, and colorfully illuminated streets and sky lines. Story boards for Kon's films are often drawn entirely by Satoshi Kon himself. In addition, Satoshi Kon often uses variations in traditional anime drawing such as simple flattening colors/color texture, transparency, and brightness to transition between alternate realities and shifting moods in more recent films like Paranoia Agent and Paprika. In these films Kon pushes some of the boudaries in drawing by illustrating impossible shape shifting between an objective reality and the worlds of dream and cyber life.

Aesthetically, scenes from Kon's films are typically colorful and visually effective. Kon's later films layer backgrounds and lighting to create papery u-kyoe effects, heavy silhouettes, and colorfully illuminated streets and sky lines. Story boards for Kon's films are often drawn entirely by Satoshi Kon himself. In addition, Satoshi Kon often uses variations in traditional anime drawing such as simple flattening colors/color texture, transparency, and brightness to transition between alternate realities and shifting moods in more recent films like Paranoia Agent and Paprika. In these films Kon pushes some of the boudaries in drawing by illustrating impossible shape shifting between an objective reality and the worlds of dream and cyber life.