In discussing his motivations and aims for his

artwork, Henri Matisse expressed, “I have always tried to hide my efforts and

wished my works to have a light joyousness of springtime which never lets

anyone suspect the labors it has cost me.” To anyone who views the French

artist’s many masterpieces, this feeling is certainly portrayed. Matisse’s

fluid use of color and expressive emotions in a wide variety of styles

characterized him as a leading artist of the modern world.

Henri Matisse, born in northern

France in 1869, abandoned his future as a lawyer when he discovered his love

for art around age twenty and moved to Paris to study it. Though originally a

traditional painter, he later developed Fauvism—characterized by wild colors,

abstraction of form, and rejection of conventional techniques—alongside artists

such as Georges Braque and Andre Derain around 1904. This “return to the purity

of means” (Museum 45), which essentially uses color to define objects as

opposed to drawing and lines, affected his art for the rest of his life. After

the Fauvism movement died out, Matisse broadened his style to encompass

sculpture, graphic art, and cutouts as well as painting and drawing, many times

exploring the themes of dance, life, music, freedom, patterns, and nature. Matisse

and Pablo Picasso pushed each other as friends and rival painters and met

weekly to socialize. Later in life, Matisse spent his time in the French

Riviera designing the Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence, or the “Matisse Chapel,”

and creating stained glass. He died in 1954 of a heart attack at the age of 84,

but his memory lives on through his art and the lighthearted, carefree feelings

it often instills in those who appreciate it.

Still Life with Two Bottles (1896)

oil on canvas, private collection

oil on canvas, private collection

This

still life exemplifies Matisse’s early traditional art. The painting is a

conventional rendering of two wine bottles, fruit, a knife, a plate, a mug, and

a table, without any distortion of color, shape, or perspective. It reflects

his early teachings.

The Joy Of Life (1905-06)

oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art

oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art

The Joy of Life is a major Fauvist painting

representing an idyllic forest filled with color and people dancing in their

natural states. He is literally trying to portray the joy in life. The

arbitrary color represents emotion, as opposed to the natural colors of the

forest, and the roles of traditional foreground and background colors are

switched, with warm colors (red, orange, yellow) making up the background and cool

colors (blue, purple) often in the foreground.

|

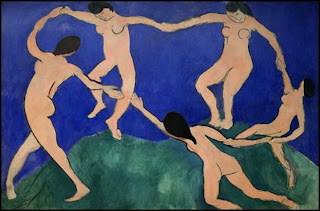

| Sketch for The Dance (1909) |

The Dance (1909)

oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art

oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art

This

piece is one of Matisse’s most famous, and it builds off of the circle of

dancing people in the background of The

Joy of Life. In this work, he simplifies the human form, disregards usual

perspective and shading, and portrays his usual theme of nature. All the

figures are connected, alluding to unity and harmony.

The Red Studio (1911)

oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art

oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art

The Red Studio is very interesting in its

nonconventional use of color. The painting portrays Matisse’s studio, complete

with several of his works in detail yet on miniature scale. The spaces between

the objects are filled in completely with a flat shade of red, with barely any

indication of placement or depth besides a thin line representing the back

corner of the room where it meets the wall. The red replaces the usual white of

the canvas but represents the same plain slate.

The Dance (1931-33)

Musee d'Art Moderne

Musee d'Art Moderne

Matisse

enjoyed working with the human form, shown in the majority of his sketches of

models and especially in his cutouts. This piece builds on Matisse’s dance

motif, with abstract human forms in dancing motion that contrast the sweeping

arch architecture where the piece is displayed. The piece is made of cutout

paper matched up with charcoal sketches, fixed to a background, and then

painted, a technique known as decoupage.

Self Portrait (1937)

charcoal on paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington

charcoal on paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Matisse,

as many artists did, experimented with creating portraits of himself. This

particular example portrays him with a very serious and even stern expression,

which conflicts with his usual happy themes in his work. Perhaps he is

depicting, as explained in the earlier quote, how he takes his art very

seriously and works hard to give it the effortless quality that viewers

perceive.

Matisse’s work has always fascinated

me. I started studying art when I was young, creating crayon pictures

and watercolor paintings full of bright colors and asking for a new box of

sharp Crayola Crayons every Christmas. I grew up expressing myself through the

use of color and have always paid more attention to it in everyday life than many of those around me. I was first introduced to Matisse in my high school art appreciation

class, and when we studied The Joy of

Life, I was intrigued by the power created by such arbitrary use of color

and loose style of painting. Further, in my college freshman year art history seminar,

we studied Picasso in depth and I learned more about Matisse through his

relationship with Picasso, especially in the Fauvist period that led to

Picasso’s African Period. I enjoy looking at Matisse’s works, appreciating his

unique style, and relating the themes to my everyday life. As Matisse stated, I also

believe that it is important to “derive happiness in oneself from a good day's

work, from illuminating the fog that surrounds us.”

Works Cited

Elderfield,

John. Matisse: In the Collection of the

Museum of Modern Art. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1978. Print.

Museum of

Modern Art. Henri Matisse. Ed.

Carolyn Lanchner. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2008. Print.

The Portable Matisse. New York: Universe

Publishing, 2002. Print.

_1931-33.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment