Despite the frenetic pace of life at Duke which makes it

hard to find breathing room and space to reflect and create, I haven’t relinquished the arts easily

because of two things. The first is my continued involvement in visual arts programming

through DUU. The second is that I remember what it was like to belong to an art

community and am trying to create that for Duke students who don’t have a formal art

community through art classes.

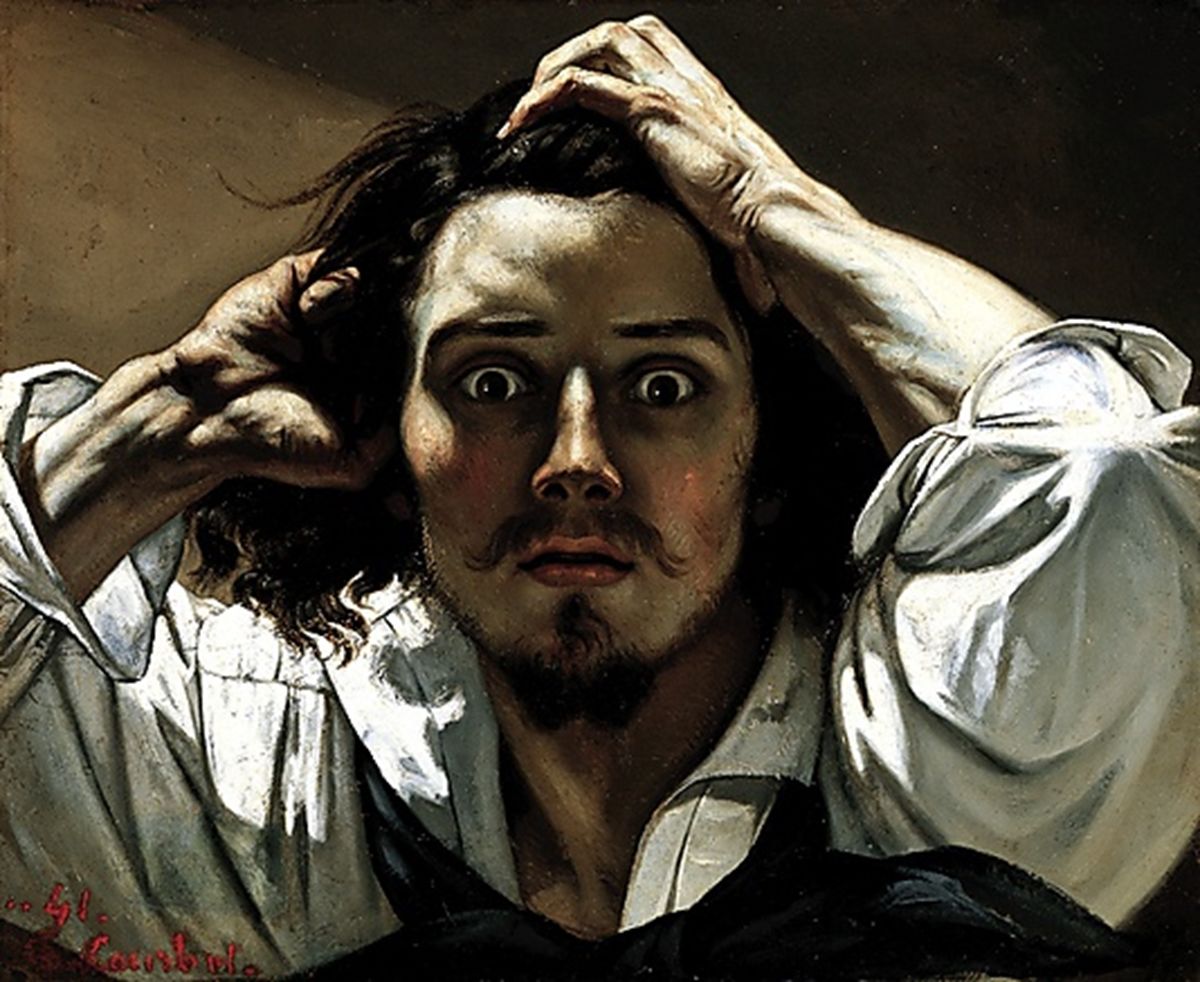

Throughout middle school and high school, I spent 3 hours a day in the art studio, the air suffused with turpentine, every available surface coated with plaster or subtly smeared with oil paint that invariably found its way onto my clothes. Before the school bell rang, my classmates would nap on the couch in the studio; between classes (and sometimes during class) we came to the studio to work on whatever hellishly ambitious assignment was due that week; after class we would put on the music, make instant noodles from the convenience store in the microwave, and paint till 11pm. Against the teacher’s orders, we left the back door in the ceramics studio open so we could sneak back in on Sunday to keep reworking our homework. I carried a sketchbook everywhere I went, documenting my life and thoughts as it happened.

Art has become core to my sense of self. As a practice and process, it’s meditative and allows me to set everything else aside to focus on the act of creation. When I flip through my sketchbooks, accumulated over the years, I have a clear chronology of my life, or at least the times in my life that I deemed memorable enough to document (when I had time, or in spite of having no time). In an environment where my strongest impulse is to rush blindly from place to place, to do the next thing and get it over and done with, art gives my life, small and insignificant as it is, structure and meaning.

Contrary to the common perception that art is an

individualistic endeavor, I think community is fundamental to the process of

art making. Peer critiques help us see what we could be doing better, and also give

us an opportunity to be inspired by other people’s work. More importantly, it

is so much easier to be committed to an artistic practice when it is bolstered

by friendship. Without peer influence, it follows that unless you have an

enormous amount of conviction and willpower, the visual arts as a proportion of

your time and your life become vanishingly small.

Against that backdrop, the work that I do with DUU VisArts

and Draw Durham—trying to build a real arts community at Duke through sustained

rather than ad-hoc programming—feels fundamentally countercultural. Creating

arts community is nothing less than asking Duke students to slow down, show up,

and take as much time as they need—not as much time as they have—to be present

to their own experience.